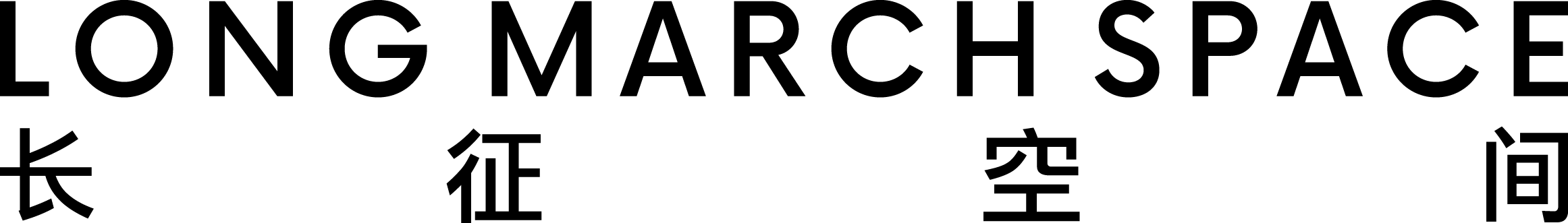

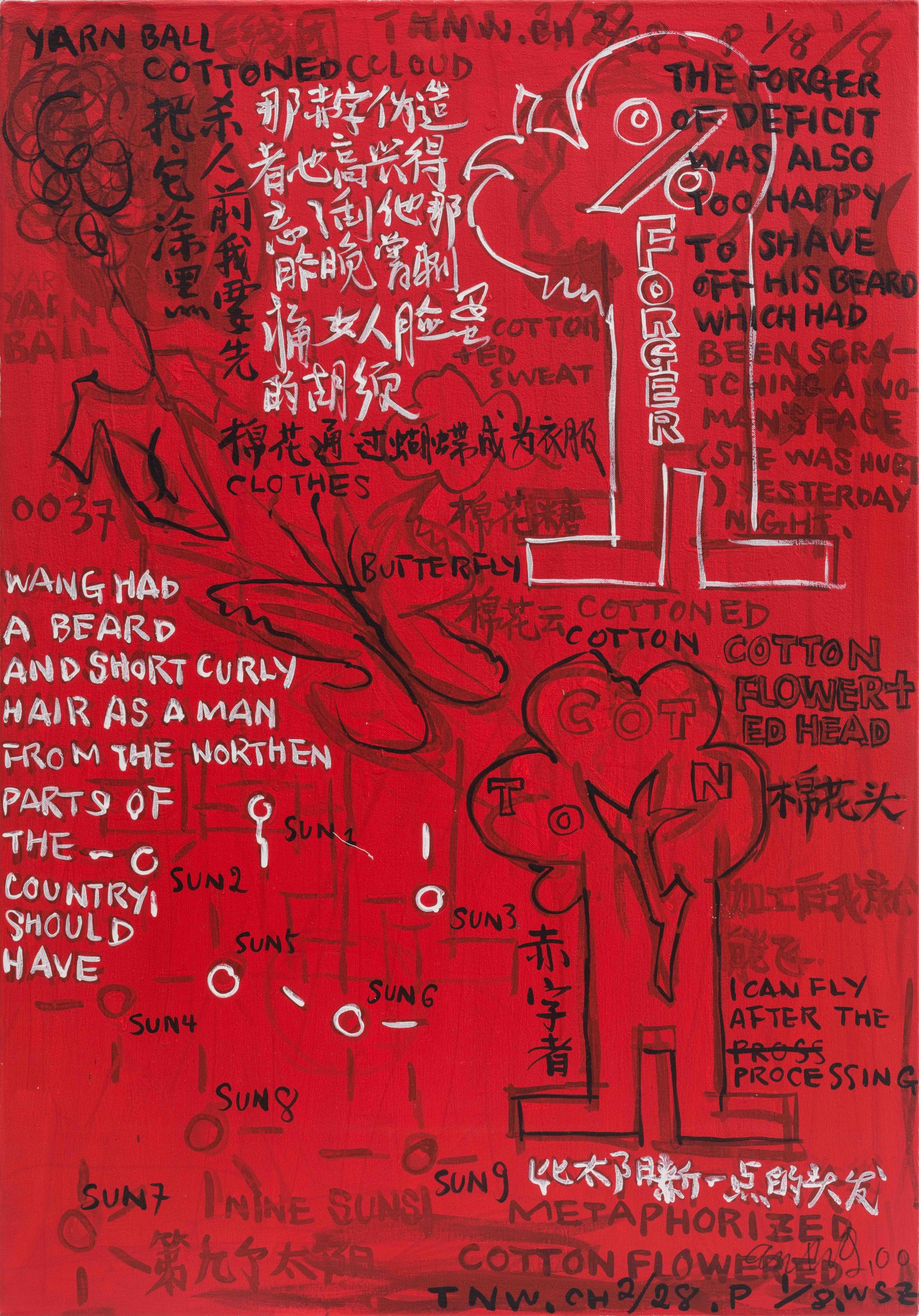

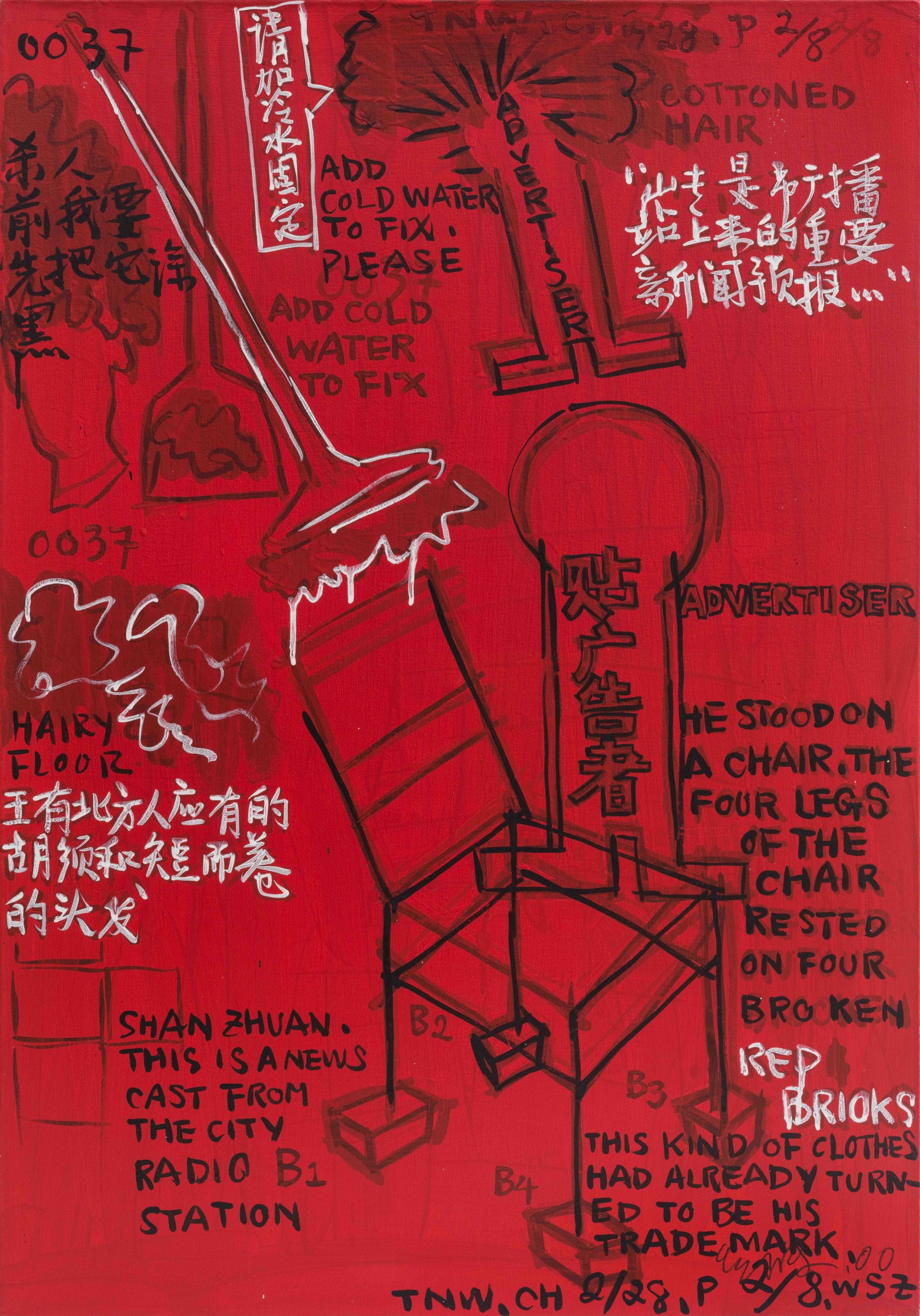

Wu Shanzhuan: Everything Starts from Today No Water (III)

Duration: 6 MAY 12:00 AM

- 5 JUNE 11:59 AM (CST), 2023

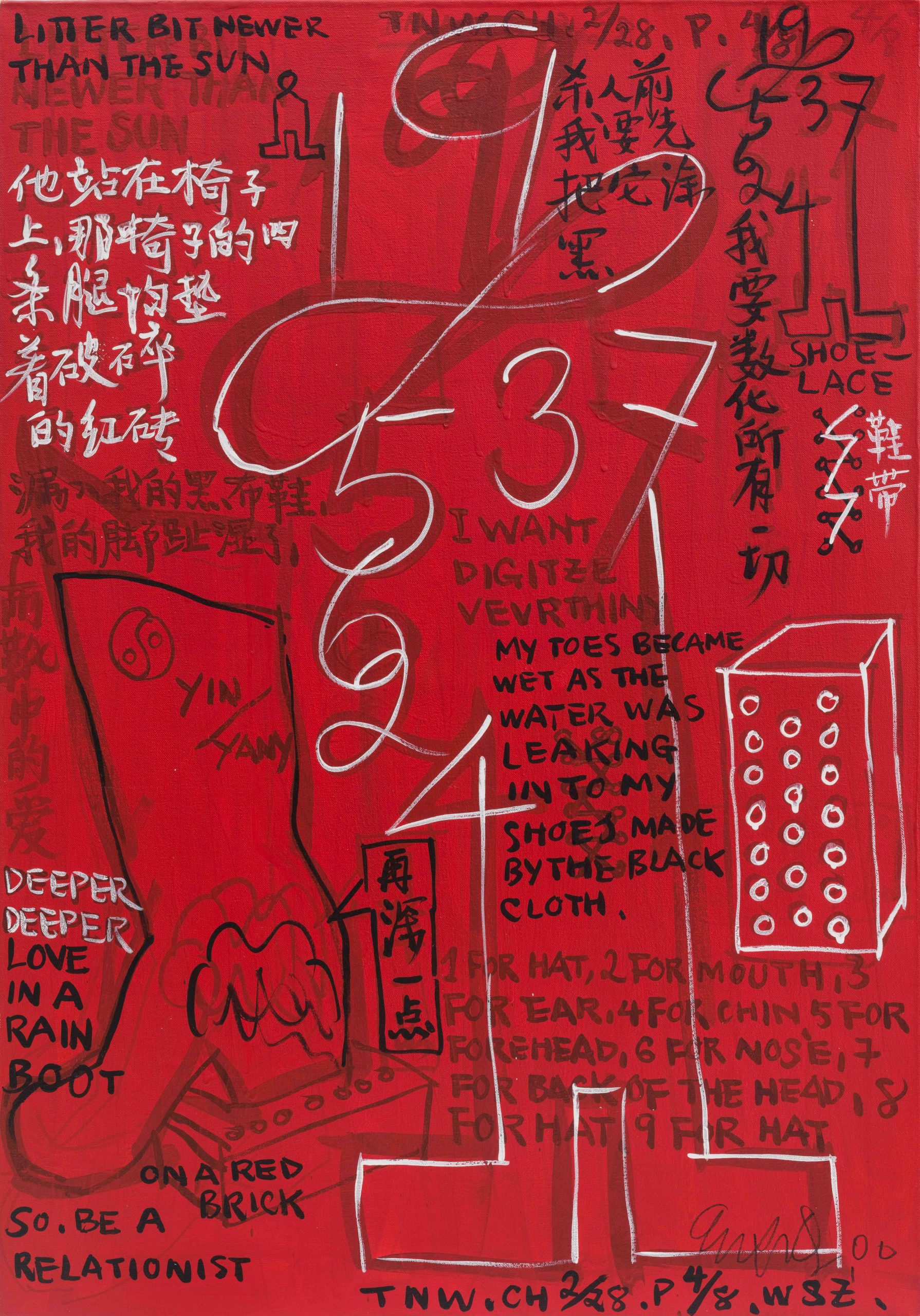

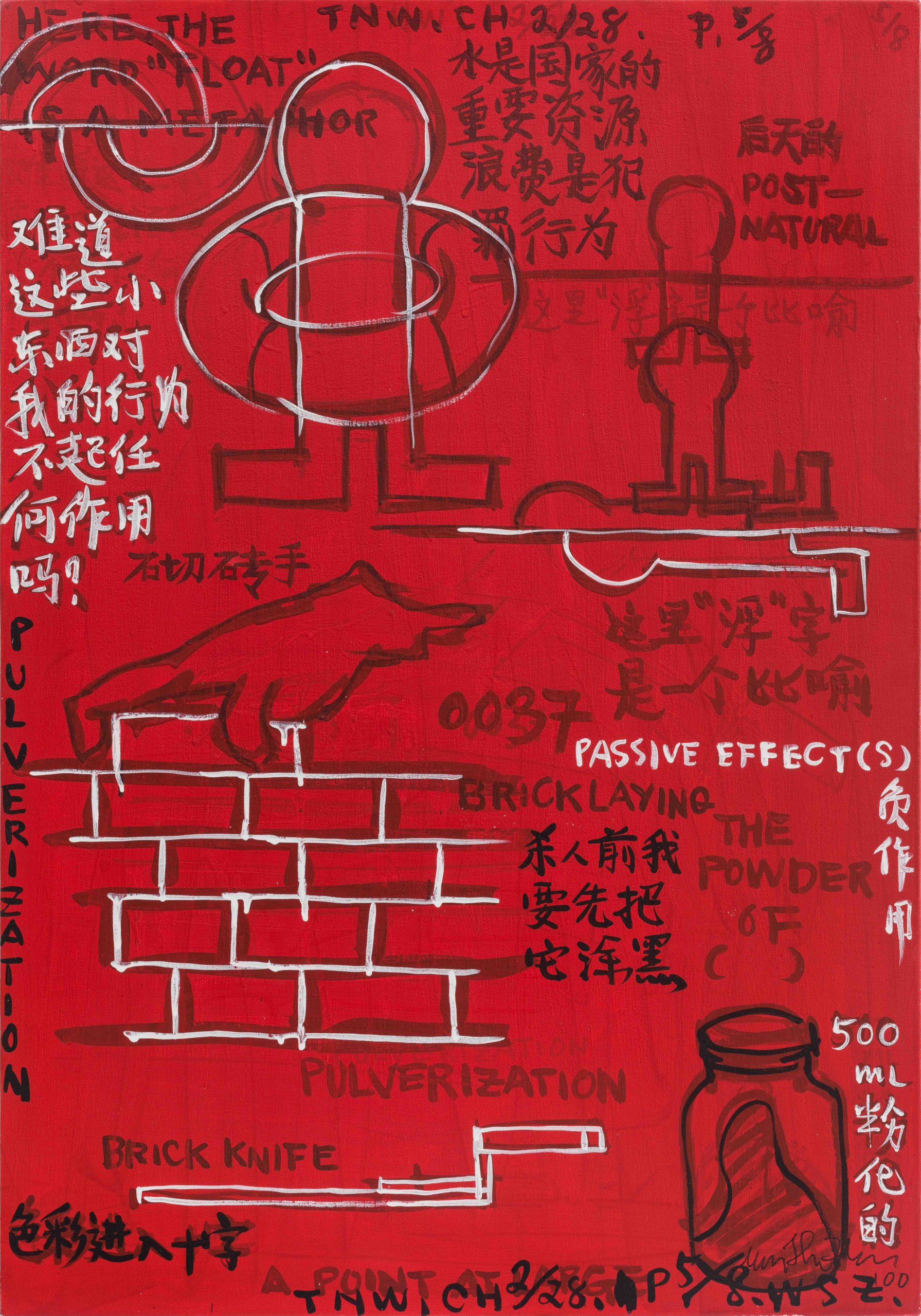

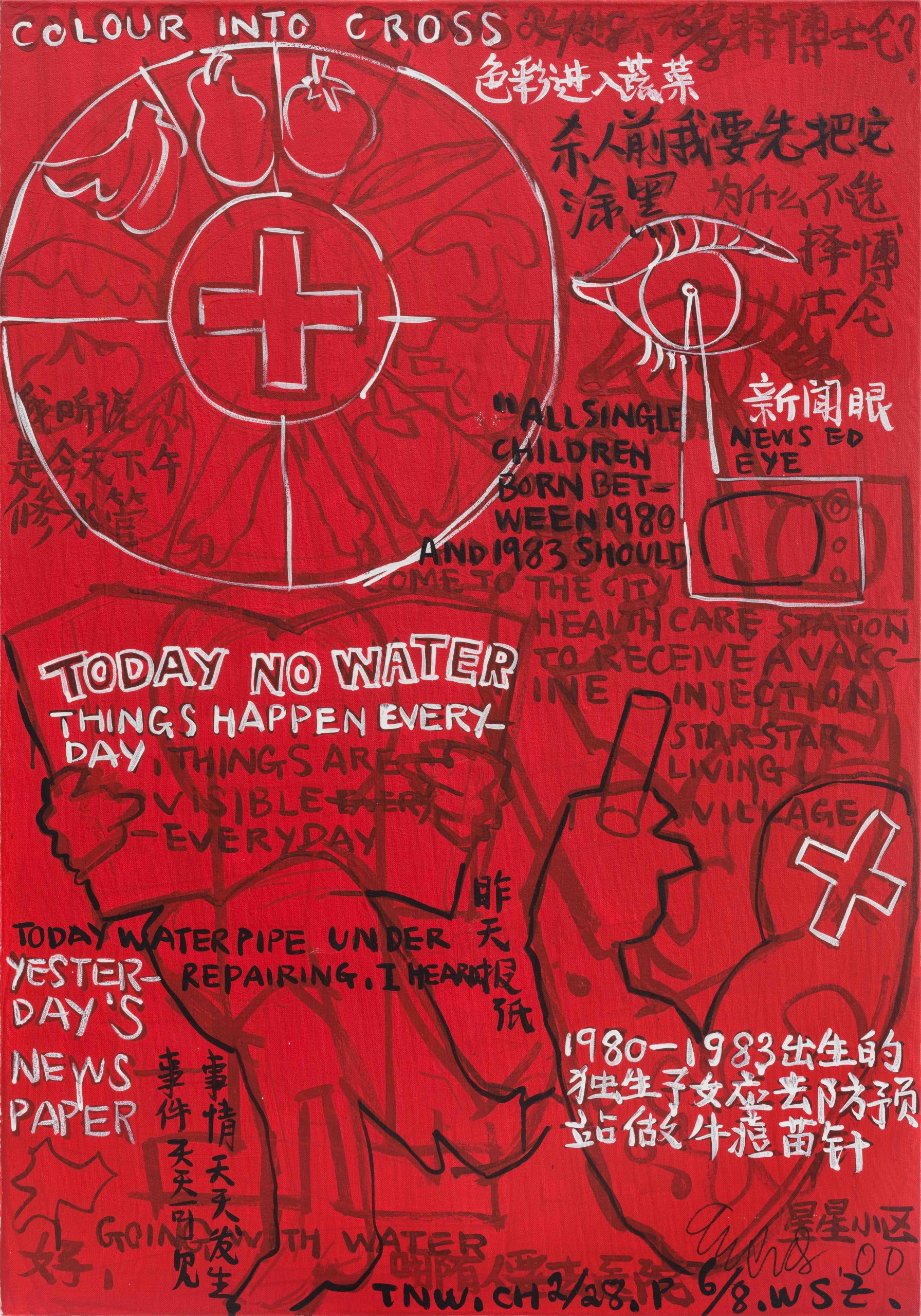

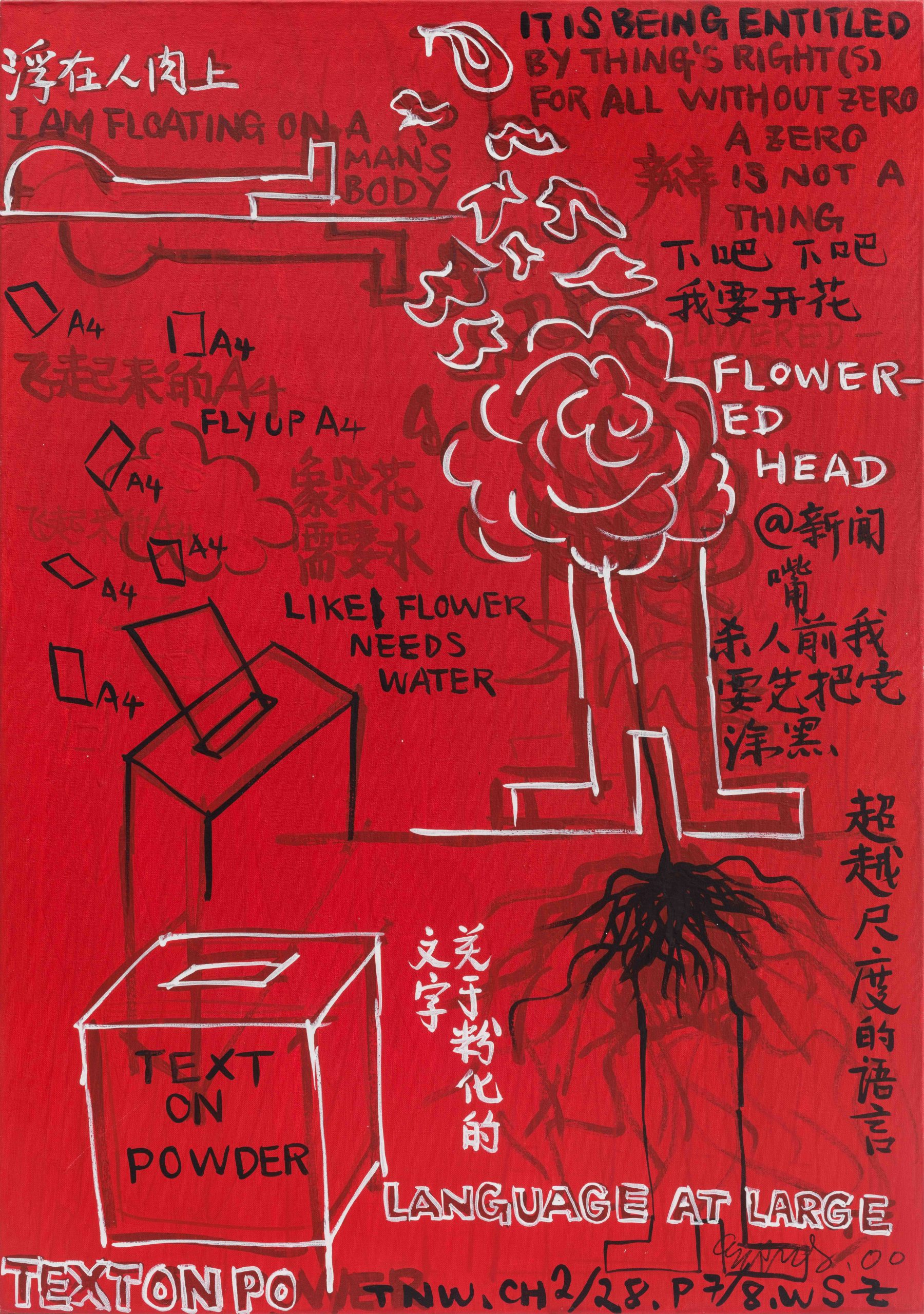

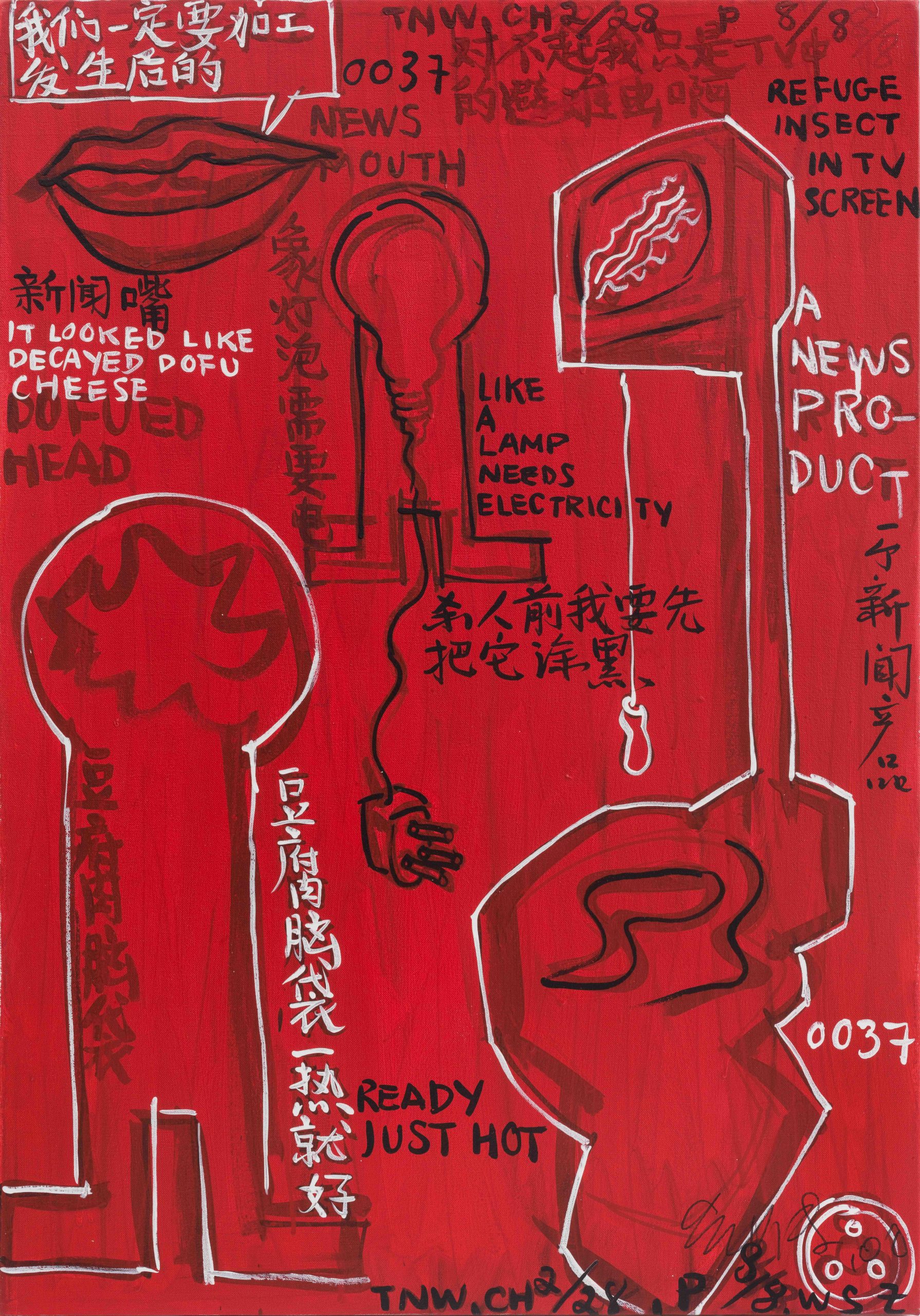

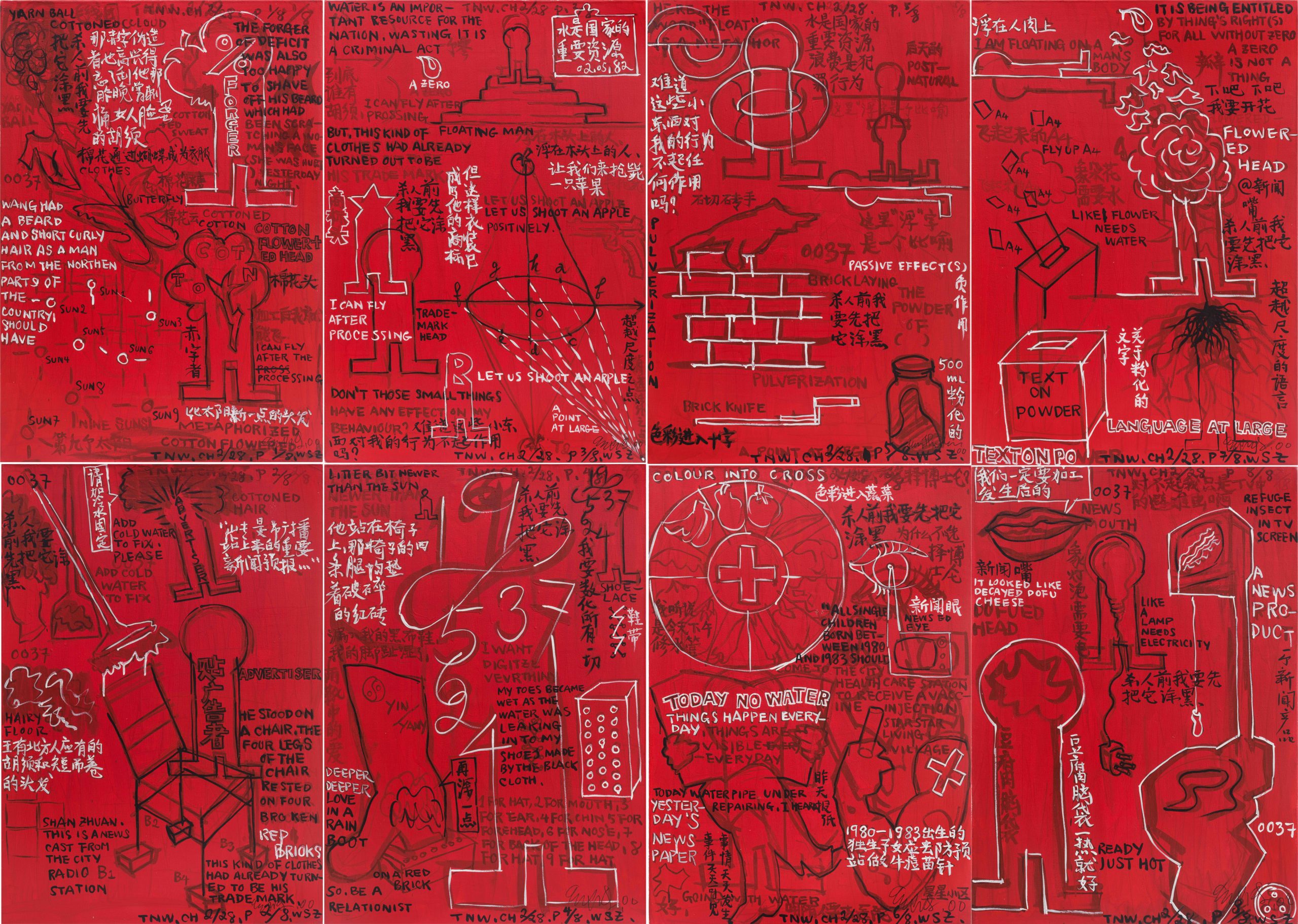

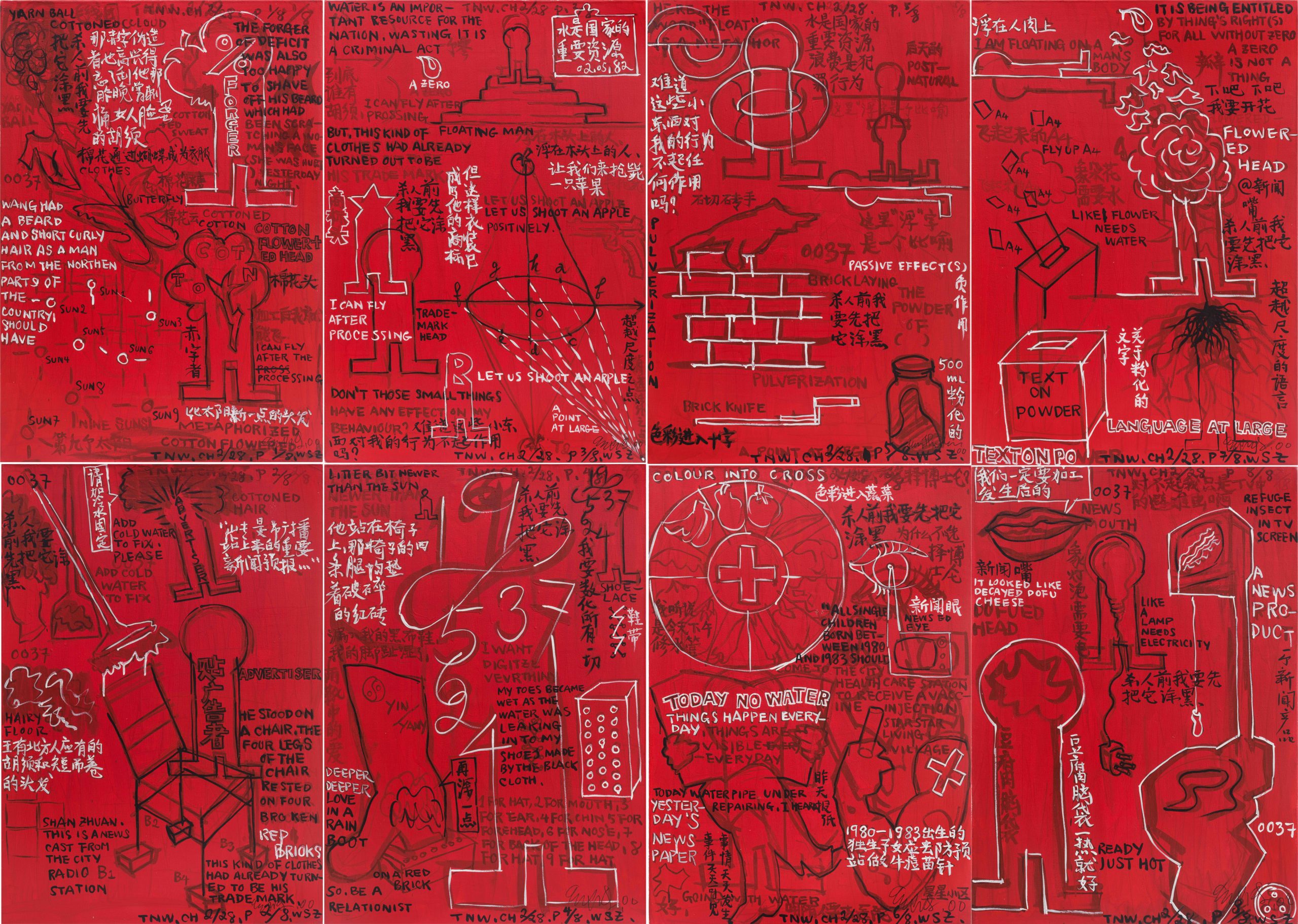

In the past two decades, post-revolutionary sentiment and experience have always been an important narrative background of contemporary Chinese art.[1] Accounts of contemporary Chinese art, whether by "the international community" or their domestic colleagues, invariably touch upon the era after the revolutions, especially the phenomenon of "post-1989", be it mass media or experts. Rejecting kitsch, subverting authorities, resisting oppression, resisting the oppressive resistance towards oppression…the post revolutionary is a repetitively dialectic discourse of struggle[2], the literary archetype of which is Kunderaesque. However, today Kundera and resistant literature does not really suffice politically. Whether it's a refusal to forget or sarcastic laughter, or Kunderaesque irony, it is still futile as resistance per se. But Wu doesn't need to resist anything. Since the 1990s, his rather post-revolutionary "red humor" has expanded into a rainbow, and is no longer oriented towards ideological captivity or authoritarian oppression, but rather a theological absurdity and an absurd theology of everyday life.

The absurdity in Wu's work is more existentialist than Kafkaesque. Kafka craved for a healthy life, but life for him was rather nebulous, devoid of center, direction and meaning, and absurdity was the consequence and side effect of his life. For Wu, however, absurdity is not so much a life experience as an ideology. More importantly, it is a point of departure. Setting sail from absurdity, Wu's politics is neither utopian nor dystopian. Whether we're talking about individual impulses towards utopia or a historical program intended for humanity at large, in utopian approaches, "nowhere" - as an inaccessible faraway locale - will always find it difficult to guarantee for itself, and inevitably turns into "somewhere"[3] but Foucauldian attempts to construct utopias are, more often than not, auto-dialectic and fall easily into the prey of opportunism.

From the writing of Today No Water to the installation work "human-machine-dragonfly-butterfly-frog", what Wu has been trying to construct is an anarchist structure, the early signs of which emerged in his 1985 big-character poster parody. This way of putting it is self-contradictory, but it gets close enough to the core of Wu's politics – it is at once anarchist and structural, which, while not directly leading to chaos, will not produce any comprehensible order either. This is Wu's view on life – either letting it be or calm resignation, either a social pleasure or existential melancholy. Everything stands between the two extremes. In terms of writing, Wu's politics is a pulverizing destruction of the structure of social currency of the Chinese language. The destruction of the space and hierarchy of the language does not necessarily constitute absurdity in expression – in this anarchist structure, absurdity is a necessary ideology, since it already is the norm of everyday life. Life is itself absurd. There is the possibility of reconciliation between everyday life and anitya (impermanence), precisely because of this.

--Excerpted from Gao Shiming's An Anarchist Structure: Wu Shanzhuan & Inga Svala Thorsdottir's Thing's Right(s) etc.

[1] I hereby thank Prof Lu Xinghua of the School of the Humanities, Tongji University, for his speech on Oct 1st 2009 at the 3rd Red Humor International reading session, which has benefited many of my views here.

[2] Placed in either the context of the post-revolutionary or that of the post-historical, the practicing space of contemporary art is located between national politics and global market. Wu Shanzhuan has been aware of the illusionary nature of the nation-state early on. As early as 1988, he wrote in the original version of Today No Water:

I don’t know what it is. I’ve heard it once bore some resemblance to a mulberry leaf…the teacher of politics said: The state is an apparatus with which one class rules another. It’s easy to remember Chinese place names, because it looks like a paper rooster or something…people living on this rooster, under the name of the People’s Republic of China, print themselves in the centre of the map and paint it pink. (Seems to me it has to be this way lest we don’t see other countries.)

“The apparatus is running & people are all clapping and laughing.”

I now know every country prints its own territory in the centre of the world map and paints it in their favorite color. From a patriotic viewpoint, they’ve successfully proven among themselves that the earth is round, yet again. Hence it also confirms our current knowledge of the earth we live on, and the fact that the point of departure for the universe we’re trying to study is also round.

[3] More importantly, there still exists the distorting force of ideology in the most utopian of works and practices. Utopian impulses and ideological manipulations are always intertwined. Utopia is also an ideology.

About Wu Shanzhuan

Wu Shanzhuan (b. 1960, China). One of the key figures of the '85 New Wave Art Movement in China, Wu Shanzhuan's practice defies use of conventional visual art terms such as "watch", "stare" and "experience" to engage with. Instead, pulling together street smartness, intellectual experimentation and the spirit of the absurd in contemporary art, Wu Shanzhuan and his collaborator Inga Svala Thorsdottir draw you into a world where "read" becomes the key term. They are not creators of visual spectacles, but rather overthrowers and discoverers of truths and propositions, as well as counterfeiters of ideology and interpreters of everyday theology.

Wu Shanzhuan defines himself as criminal, intermediary, tourist and labor. The works Wu Shanzhuan creates are not the granted artworks but rather "Wu's Things". From the large number of "Wu's Things" made in the early 1990s, we see a desire for full opening and "transcending the boundaries" and his obsession with mathematics and logic which brings a strange sense of truth to his works. For a society dictated by a variety of faiths and customs, this is an "adulterated" truth. Wu never tires of quoting from Sartre: "People are a bundle of useless passion". The use for his useless passion is to find "useless truths". For more than 20 years, Wu Shanzhuan has used the forumulas "pseudo-words", "thing's right(s)", "parthenogenesis", "secondhand water", "tourist information", "perfect bracket" and "bird before peace", all of which are "useless truths", to weave his personal ideology. This ideology constitutes a profound critique to the system of concepts and experiences that we are accustomed to.

In the era when conceptual art generally faces a rethink, the works attest a vibrancy of concept and the power of thoughts. It is a rich collection of intriguing humor and sharp wit, spontaneous anti-metaphysical actions, insights into everyday politics, sensitivity to invisible workings of power systems and adherence to the fundamental state of democracy.

Wu Shanzhuan: Everything Starts from Today No Water (III)

Duration: 6 MAY 12:00 AM

- 5 JUNE 11:59 AM (CST), 2023

In the past two decades, post-revolutionary sentiment and experience have always been an important narrative background of contemporary Chinese art.[1] Accounts of contemporary Chinese art, whether by "the international community" or their domestic colleagues, invariably touch upon the era after the revolutions, especially the phenomenon of "post-1989", be it mass media or experts. Rejecting kitsch, subverting authorities, resisting oppression, resisting the oppressive resistance towards oppression…the post revolutionary is a repetitively dialectic discourse of struggle[2], the literary archetype of which is Kunderaesque. However, today Kundera and resistant literature does not really suffice politically. Whether it's a refusal to forget or sarcastic laughter, or Kunderaesque irony, it is still futile as resistance per se. But Wu doesn't need to resist anything. Since the 1990s, his rather post-revolutionary "red humor" has expanded into a rainbow, and is no longer oriented towards ideological captivity or authoritarian oppression, but rather a theological absurdity and an absurd theology of everyday life.

The absurdity in Wu's work is more existentialist than Kafkaesque. Kafka craved for a healthy life, but life for him was rather nebulous, devoid of center, direction and meaning, and absurdity was the consequence and side effect of his life. For Wu, however, absurdity is not so much a life experience as an ideology. More importantly, it is a point of departure. Setting sail from absurdity, Wu's politics is neither utopian nor dystopian. Whether we're talking about individual impulses towards utopia or a historical program intended for humanity at large, in utopian approaches, "nowhere" - as an inaccessible faraway locale - will always find it difficult to guarantee for itself, and inevitably turns into "somewhere"[3] but Foucauldian attempts to construct utopias are, more often than not, auto-dialectic and fall easily into the prey of opportunism.

From the writing of Today No Water to the installation work "human-machine-dragonfly-butterfly-frog", what Wu has been trying to construct is an anarchist structure, the early signs of which emerged in his 1985 big-character poster parody. This way of putting it is self-contradictory, but it gets close enough to the core of Wu's politics – it is at once anarchist and structural, which, while not directly leading to chaos, will not produce any comprehensible order either. This is Wu's view on life – either letting it be or calm resignation, either a social pleasure or existential melancholy. Everything stands between the two extremes. In terms of writing, Wu's politics is a pulverizing destruction of the structure of social currency of the Chinese language. The destruction of the space and hierarchy of the language does not necessarily constitute absurdity in expression – in this anarchist structure, absurdity is a necessary ideology, since it already is the norm of everyday life. Life is itself absurd. There is the possibility of reconciliation between everyday life and anitya (impermanence), precisely because of this.

--Excerpted from Gao Shiming's An Anarchist Structure: Wu Shanzhuan & Inga Svala Thorsdottir's Thing's Right(s) etc.

[1] I hereby thank Prof Lu Xinghua of the School of the Humanities, Tongji University, for his speech on Oct 1st 2009 at the 3rd Red Humor International reading session, which has benefited many of my views here.

[2] Placed in either the context of the post-revolutionary or that of the post-historical, the practicing space of contemporary art is located between national politics and global market. Wu Shanzhuan has been aware of the illusionary nature of the nation-state early on. As early as 1988, he wrote in the original version of Today No Water:

I don’t know what it is. I’ve heard it once bore some resemblance to a mulberry leaf…the teacher of politics said: The state is an apparatus with which one class rules another. It’s easy to remember Chinese place names, because it looks like a paper rooster or something…people living on this rooster, under the name of the People’s Republic of China, print themselves in the centre of the map and paint it pink. (Seems to me it has to be this way lest we don’t see other countries.)

“The apparatus is running & people are all clapping and laughing.”

I now know every country prints its own territory in the centre of the world map and paints it in their favorite color. From a patriotic viewpoint, they’ve successfully proven among themselves that the earth is round, yet again. Hence it also confirms our current knowledge of the earth we live on, and the fact that the point of departure for the universe we’re trying to study is also round.

[3] More importantly, there still exists the distorting force of ideology in the most utopian of works and practices. Utopian impulses and ideological manipulations are always intertwined. Utopia is also an ideology.

About Wu Shanzhuan

Wu Shanzhuan (b. 1960, China). One of the key figures of the '85 New Wave Art Movement in China, Wu Shanzhuan’s practice defies use of conventional visual art terms such as “watch”, “stare” and “experience” to engage with. Instead, pulling together street smartness, intellectual experimentation and the spirit of the absurd in contemporary art, Wu Shanzhuan and his collaborator Inga Svala Thorsdottir draw you into a world where “read” becomes the key term. They are not creators of visual spectacles, but rather overthrowers and discoverers of truths and propositions, as well as counterfeiters of ideology and interpreters of everyday theology.

Wu Shanzhuan defines himself as criminal, intermediary, tourist and labor. The works Wu Shanzhuan creates are not the granted artworks but rather “Wu’s Things”. From the large number of “Wu’s Things” made in the early 1990s, we see a desire for full opening and “transcending the boundaries” and his obsession with mathematics and logic which brings a strange sense of truth to his works. For a society dictated by a variety of faiths and customs, this is an “adulterated” truth. Wu never tires of quoting from Sartre: “People are a bundle of useless passion”. The use for his useless passion is to find “useless truths”. For more than 20 years, Wu Shanzhuan has used the forumulas “pseudo-words”, “thing’s right(s)”, “parthenogenesis”, “secondhand water”, “tourist information”, “perfect bracket” and “bird before peace”, all of which are “useless truths”, to weave his personal ideology. This ideology constitutes a profound critique to the system of concepts and experiences that we are accustomed to.

In the era when conceptual art generally faces a rethink, the works attest a vibrancy of concept and the power of thoughts. It is a rich collection of intriguing humor and sharp wit, spontaneous anti-metaphysical actions, insights into everyday politics, sensitivity to invisible workings of power systems and adherence to the fundamental state of democracy.